Photographer Harrison Funk

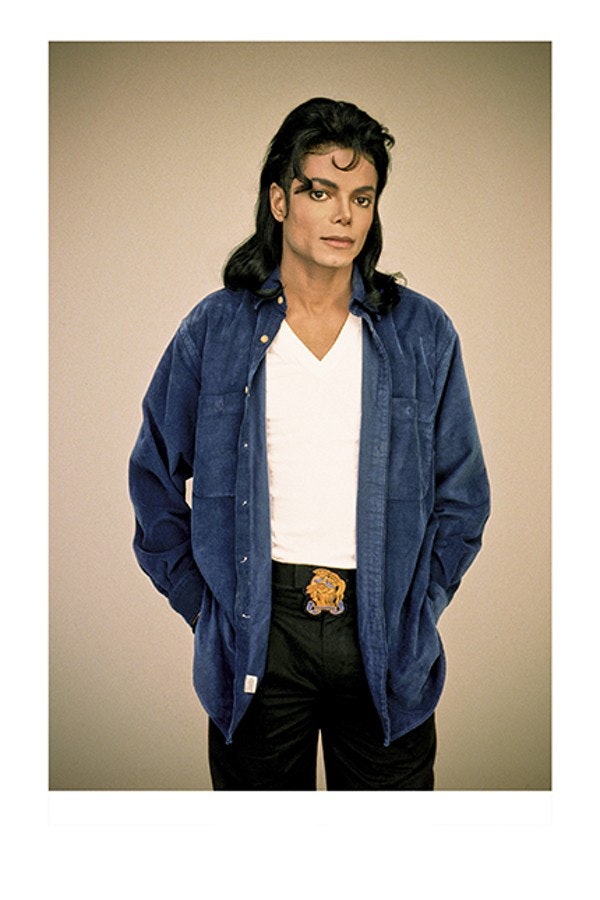

Harrison Funk remembers being captivated by Michael Jackson’s eyes. “Michael had the most beautiful eyes I’ve ever photographed,” he told me recently. “They were large. They were expressive. They were deep. I don’t mean that physically. It was a picture into his soul. I think Michael, he knew in every picture what he wanted to convey. Even when he was completely natural he could convey a message to the camera.”

In the early 1980s Funk began shooting Michael and continued on and off until his death five years ago on June 25, 2009. Funk was in his twenties when he made his first shot of Michael, before the singer launched his solo career. He had been invited to a party at New York City’s Tavern on the Green, and at one point during the night he found himself shooting pictures of Michael and the rest of the Jackson family backstage. Shortly afterward, Funk got a call from Michael’s publicist, inviting him to Los Angeles. Without promise of a job or even reimbursement, Funk got on the plane.

He remembers the day that he and Michael connected—really connected—for the first time. Tito Jackson’s kids were playing in a softball game, and while a couple of the brothers hung out on the sidelines, Michael sat by himself in a parked car down the block. When he saw Funk approach, Michael told him to get in and the two sat talking about “everything in the world, and baseball.”

Michael used to do something when he wanted the attention of the camera. He would practice his moves. Like when he’d go ‘hee hee,’ and I could tell that was the moment to pick up my camera and shoot.”

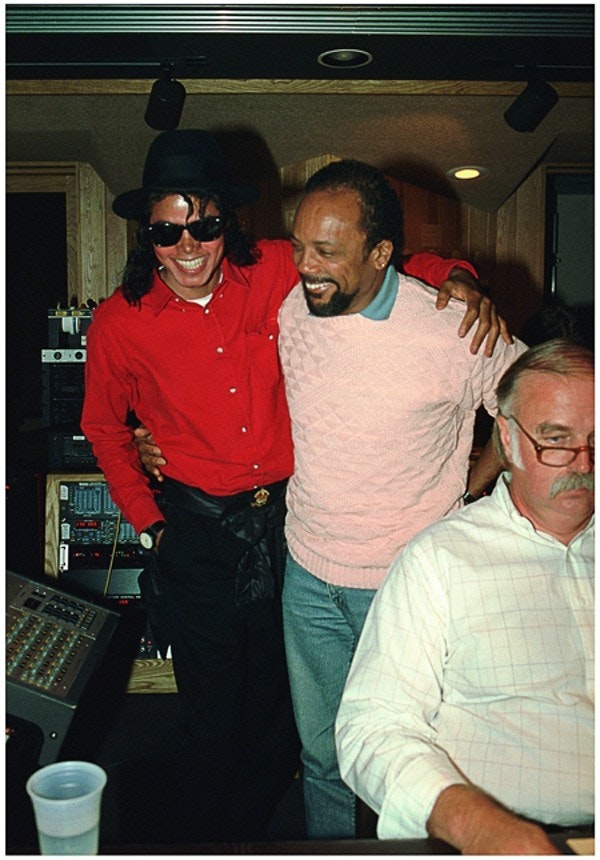

Funk chronicled Jackson’s career, starting with the Jacksons’ Victory Tour in 1984 and Michael’s first solo tour, Bad (1987-89). “He taught me so much about observing, seeing the moment and capturing the moment,” Funk said. “He taught me so much about perfection and Michael was a perfectionist. He wanted everything to be just so, even when it was spontaneous, it was just so. That was part of his brilliance, the ability to make that happen without any effort.”

Access and trust are key to making documentary images, especially with publicity-conscious celebrities. “I was just myself,” Funk said. “There was no pretense. I am who I am. I was open, and they knew that no picture would leave my hands without approval. And it got to the point to the middle of the tour where I was able to approve images. They trusted me.”

I think that image represents a slice of the 80s and the culture of the 80s that’s unbelievable. Here you have the first African American man running for president, Jesse, and the most famous human being alive, and Jesse is giving him advice.”

Funk remembers vividly the day he photographed Jesse Jackson and Michael Jackson. Jesse was running for president, and he was planning to attend an NAACP convention near a location where Michael would be performing. The candidate asked for a meeting with the pop star to talk about how few black workers Michael had on his crew.

Funk and Jesse Jackson’s personal photographer, Bruce Talamon, sat on the floor shooting as the two Jacksons talked, and suddenly Jesse turned and dismissed his photographer. “’Alright, photo op’s over.’ Michael turns to me and says, ‘Harrison, stay.’” Turning back to Jesse, Michael said, ‘My photographer shoots everything.’”

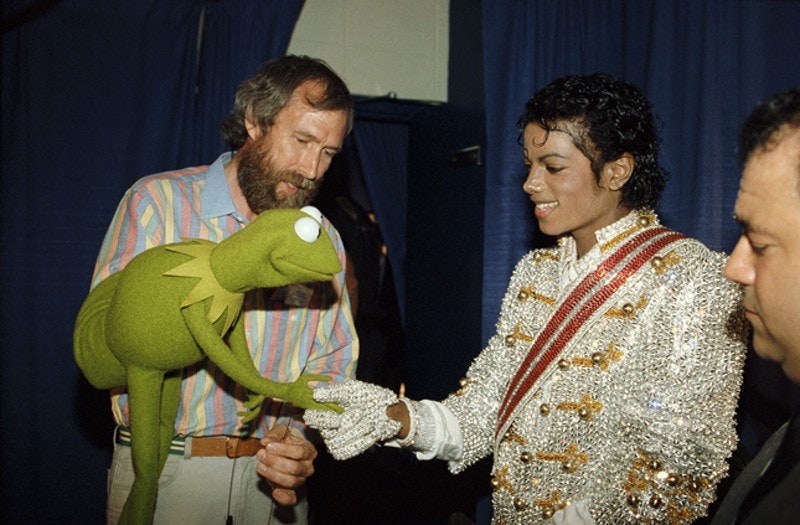

“He got to meet Kermit!”

Musicians started restricting photographic access in the 80s, Funk remembers. “They didn’t want to be photographed snorting a pound of coke.” But Michael Jackson and his family were different, and to them, Funk was a friend. They welcomed him onto the tour and into their lives.

“He liked to play practical jokes, and he liked to have fun. He was a big kid. There was one food fight where I wore a bucket of shrimp...after they poured it all over me,” Funk said.

This week, in Los Angeles, is Michael week, Funk said, and he’s been documenting the gathering crowds who considered Michael Jackson a prophet. Funk still grieves for his friend, but quietly, away from the fans who gather to pay tribute.

Source: newrepublic.com/article/118407/michael-jackson-photographer-harrison-funk-remembers

__________________________________________________

“Him and Jermaine (Jackson) loved putting on their own makeup…. It wasn’t so much femininity on Michael’s part as androgyny – he was fluid around gender. Michael had no interest in assigning a gender to anybody. He didn’t overtly identify as one particular gender,” Funk told the Guardian.

However, when Jackson had kids –Prince, Paris and Blanket– his image changed to that “of father”.

“He became a strong man in that sense,” Funk added.

The photographer also revealed the “Beat It” hitmaker became prone to dramatic outbursts during his Victory Tour of the US and Canada in 1984.

”Michael had very demanding moments. If he didn’t like something, he let you know. Michael was never ridiculing to me ever, but if someone messed up the design of his stage, then he would yell at them. He expected perfection.” During the 1990s, Jackson’s music became more socially conscious, with hits such as “Earth Song” and “Black or White”.

However, he also attracted controversy when he struck a Jesus-like pose in one of Funk’s most famous photographs.

“People say Michael had a Jesus complex, but that p***es me off, as it just wasn’t true. There was a practical reason for me taking that photo.

”Michael had huge hands and I wanted to make the most of them as they were expressive – and a good way for him to embrace the world. At that stage, his whole existence was geared towards healing the world, so having big, expressive hands was a very important way to speak to the people,” Funk said.