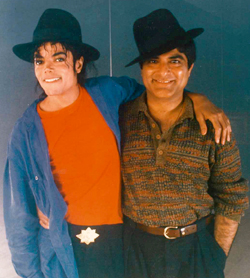

Deepak Chopra - A Tribute to My Friend, Michael Jackson

Michael Jackson will be remembered, most likely, as a shattered icon, a pop genius who wound up a mutant of fame. That’s not who I will remember, however. His mixture of mystery, isolation, indulgence, overwhelming global fame, and personal loneliness was intimately known to me. For twenty years I observed every aspect, and as easy as it was to love Michael — and to want to protect him — his sudden death yesterday seemed almost fated.

Two days previously he had called me in an upbeat, excited mood. The voice message said, “I’ve got some really good news to share with you.” He was writing a song about the environment, and he wanted me to help informally with the lyrics, as we had done several times before. When I tried to return his call, however, the number was disconnected. (Terminally spooked by his treatment in the press, he changed his phone number often.) So I never got to talk to him, and the music demo he sent me lies on my bedside table as a poignant symbol of an unfinished life.

When we first met, around 1988, I was struck by the combination of charisma and woundedness that surrounded Michael. He would be swarmed by crowds at an airport, perform an exhausting show for three hours, and then sit backstage afterward, as we did one night in Bucharest, drinking bottled water, glancing over some Sufi poetry as I walked into the room, and wanting to meditate.

That person, whom I considered (at the risk of ridicule) very pure, still survived — he was reading the poems of Rabindranath Tagore when we talked the last time, two weeks ago. Michael exemplified the paradox of many famous performers, being essentially shy, an introvert who would come to my house and spend most of the evening sitting by himself in a corner with his small children. I never saw less than a loving father when they were together (and wonder now, as anyone close to him would, what will happen to them in the aftermath).

Michael’s reluctance to grow up was another part of the paradox. My children adored him, and in return he responded in a childlike way. He declared often, as former child stars do, that he was robbed of his childhood. Considering the monstrously exaggerated value our society places on celebrity, which was showered on Michael without stint, the public was callous to his very real personal pain. It became another tawdry piece of the tabloid Jacko, pictured as a weird changeling and as something far more sinister.

It’s not my place to comment on the troubles Michael fell heir to from the past and then amplified by his misguided choices in life. He was surrounded by enablers, including a shameful plethora of M.D.s in Los Angeles and elsewhere who supplied him with prescription drugs. As many times as he would candidly confess that he had a problem, the conversation always ended with a deflection and denial. As I write this paragraph, the reports of drug abuse are spreading across the cable news channels. The instant I heard of his death this afternoon, I had a sinking feeling that prescription drugs would play a key part.

The closest we ever became, perhaps, was when Michael needed a book to sell primarily as a concert souvenir. It would contain pictures for his fans but there would also be a text consisting of short fables. I sat with him for hours while he dreamily wove Aesop-like tales about animals, mixed with words about music and his love of all things musical. This project became “Dancing the Dream” after I pulled the text together for him, acting strictly as a friend. It was this time together that convinced me of the modus vivendi Michael had devised for himself: to counter the tidal wave of stress that accompanies mega-stardom, he built a private retreat in a fantasy world where pink clouds veiled inner anguish and Peter Pan was a hero, not a pathology.

This compromise with reality gradually became unsustainable. He went to strange lengths to preserve it. Unbounded privilege became another toxic force in his undoing. What began as idiosyncrasy, shyness, and vulnerability was ravaged by obsessions over health, paranoia over security, and an isolation that grew more and more unhealthy. When Michael passed me the music for that last song, the one sitting by my bedside waiting for the right words, the procedure for getting the CD to me rivaled a CIA covert operation in its secrecy.

My memory of Michael Jackson will be as complex and confused as anyone’s. His closest friends will close ranks and try to do everything in their power to insure that the good lives after him. Will we be successful in rescuing him after so many years of media distortion? No one can say. I only wanted to put some details on the record in his behalf. My son Gotham traveled with Michael as a roadie on his “Dangerous” tour when he was seventeen. Will it matter that Michael behaved with discipline and impeccable manners around my son? (It sends a shiver to recall something he told Gotham: “I don’t want to go out like Marlon Brando. I want to go out like Elvis.” Both icons were obsessions of this icon.)

His children’s nanny and surrogate mother, Grace Rwaramba , is like another daughter to me. I introduced her to Michael when she was eighteen, a beautiful, heartwarming girl from Rwanda who is now grown up. She kept an eye on him for me and would call me whenever he was down or running too close to the edge. How heartbreaking for Grace that no one’s protective instincts and genuine love could avert this tragic day. An hour ago she was sobbing on the telephone from London. As a result, I couldn’t help but write this brief remembrance in sadness. But when the shock subsides and a thousand public voices recount Michael’s brilliant, joyous, embattled, enigmatic, bizarre trajectory, I hope the word “joyous” is the one that will rise from the ashes and shine as he once did.

Read more at https://www.beliefnet.com/columnists/intentchopra/2009/06/a-tribute-to-my-friend-michael.html#3T03e4S8yI6ZPKI3.99

Gotham Chopra - Remembering my friend Michael Jackson

I was a junior in high school when my friend Michael Jackson asked me to go on tour with him. He was spending the summer in Europe staging the largest ever (at the time) rock tour for his latest album DANGEROUS. I begged and pleaded with my parents to let me go. We’d known Michael for a few years by then and grown quite close. He’d even come and stayed at our house in suburban Boston for a few days. Who could forget the time he clumsily tried to make his bed in the guestroom in the morning in an effort to impress my mother so he might be invited back? Or the ill-fated breakfast he tried to cook for my sister and I that we forced down our throats with strained smiles as he carefully watched us? Aside from being the biggest celebrity on the planet, he seemed like a pretty good guy so eventually my parents relented and let me go.

To describe it in one word: impossibly awesome (because one word is not nearly enough). To be seventeen and the sidekick of the greatest rockstar the world had ever known was indescribable. Paris, Rome, London, Munich, Athens and more. Every city we went to essentially shut down to host him. Where Michael roamed, a million cameras followed. A buzz reverberated and the bright light of fame trailed. And I felt the halo effect, often donning one of his iconic fedoras, his signature sunglasses, and one of the countless slick tour jackets Pepsi supplied us with. Private planes, police escorts, marching soldiers (an inexplicable MJ favorite), Michael was more than happy to share his celebrity because he had more than he’d ever know what to do with. He joked that I could ride “shotgun” with him anytime I liked. He knew I was living vicariously through him and he was happy for it.

Arriving to stadiums hours before showtime, while he’d have to go through elaborate pre-show routines and wardrobe sessions, I’d wander out onto the stage where dozens upon dozens of sound techs, engineers, and roadies would be rigging the massive stage and prepping the show. Even four or five hours before showtime, thousands of fans would push as far forward as possible so as to get as close to MJ when the show began. You’ve seen the videos of crazy fans, dehydrated and dazed, having to be dragged out of the crowd by hustling paramedics. I saw it up close and personal – even got involved once or twice when fans started dropping by the dozens.

During the show itself, sometimes I’d hang around just off the stage watching Michael kill it. The man knew how to perform and it was like a meditation to just to witness it. At other times, I’d hang in his dressing room, outfitted to the nines with candy, orange juice, and video games.

After the show, Michael would retreat back to the dressing room too and then be forced to stand around awkwardly and greet VIPs, celebrity guests, sponsors and others who’d earned backstage privileges. It was easy to see that he was far more comfortable singing and dancing in front of a 100,000 strong than socializing with a dozen.

After those formalities, he and I would retreat back to his hotel, usually the biggest and best suite in the whole city. Michael almost always had the place stocked with old movies, more candy, and more orange juice. Even as thousands of adoring fans chanted his name from the streets below, we’d chat about music, movies, video games, girls, and occasionally the meaning of life.

But then something unexpected happened. The awesomeness wore off for me. Believe it or not, I started to get bored of sitting up in that suite with just MJ. And then I started to feel claustrophobic. I was seventeen years old, in freaking Europe, surrounded by a rock band, sexy dancers who could bend in all sorts of ways and backup singers who hit octaves I fantasized about. They liked to rage every night after the show and openly talked about their exploits the following day. Soon enough, I gained the courage to ask Michael if he minded if I slipped out with some of the others after his shows.

Not only did he say it was okay, he encouraged me. Outfitted with his fedora, sunglasses, and tour jackets, getting the best table at the best restaurants, into the VIP sections of the hottest clubs, and the adulation of all the local girls was easier than could be imagined. Often when I got back from a night on the town, Michael would call me in my hotel room and summon me. I’d head up to his suite and proceed to narrate my night’s misadventures to him and debrief him on all the latest gossip surrounding his band. I didn’t really need to dramatize my exploits, but I did anyway because I knew that he was living vicariously through me and I was happy for it.

It’s a cliché to say that your highschool summers are the most memorable of your life, but I challenge anyone to say how mine could not be. For years, I wore the badge of that summer and my many exploits over it boldly and boastfully. Then of course, as time passed and Michael became embroiled in scandals involving teen boys, all of a sudden my summer as his teen sidekick didn’t have the same glamour to it. Now it was a stigma, something I treasured but certainly did not tout.

Over the years my brotherhood with Michael evolved. When I went to college in NYC and lived uptown, he lived at the Four Seasons in midtown and I’d see him regularly, sharing with him collegiate exploits and adventures. Years later when he became a father, he invited me over to Neverland to see “the greatest thing he ever created” – his son Prince. More time passed. I watched as he endured the agony of his dramatic fall from grace, his resurrection through his children Prince, Paris, and Blanket, and then once again the agony of his descent into the shadows of things he couldn’t control.

During the last years of his life, I got to see his creativity up close and personal once again. He and I were working on a graphic novel together entitled THE FATED. He had big plans for it. One day he wanted to direct it as a film, impress his mentor Steven Spielberg, and have his favorite actor Will Smith be in it. It was classic MJ in terms of process, intense at times, with intermittent months of total inaction in between. The story of an iconic Rockstar worn out by the agony of his fame, driven to the most desperate measures, only to discover that his super-stardom has him “fated” for far more than just fame and fortune. Of course, I eventually realized Michael was giving me a window into his own personal allegory and I felt privileged to help record it. Sadly, we never were able to complete the story and I was left instead with an eerie tale without a proper ending (note: I hope with the assistance of Michael’s Estate – in the hands of some very capable and conscious stewards – that we’ll one day be able to share The Fated with all the dignity it and Michael deserves).

Like The Fated, we never got to see a proper ending to Michael’s tale. Instead there’s a tangled legacy, the bright light of fame shining over the tumbled necropolis of unfounded allegations twisted around the neverending tenderness for his own children. it’s funny to me how in the last year, in death Michael has been canonized by many of the same commentators who were so relentless in tearing him down while he lived. He’d see the irony in it and call them bad names – the man could curse like a drunken sailor.

One night while on that tour with him, toward the end when I was getting ready to go back to school and the real world, Michael asked me if I was glad that I had come, even though I couldn’t stay for the whole tour. He knew I was sad that I wouldn’t get to stay until the very end. Still, it was an insane question and I told him so. “Are you kidding?” I said. “Every second I was here with you was a privilege. Thank you for letting me ride shotgun even for a little while.”

Read more at www.beliefnet.com/columnists/intentchopra/2010/06/remembering-my-friend-michael.html#GymLlcIz67pWIZU3.99