Michael Jackson´s experience of racism

In an early years, as an adult, and after his death (right in front of our eyes):

La Toya Jackson in her book Growing Up In The Jacksons:

Suddenly he heard, “Help! Help!” It was Michael, yelling from inside the store. Bursting through the door, Bill saw my brother curled up on the floor and a white man kicking him viciously in the head and stomach, screaming with blood curdling venom, “I hate all of you! I hate you!” Over and over he called Michael a nigger.

Bill, a tall, middle aged black man, subdued the attacker and helped up Michael, who was crying and bleeding from several deep cuts. “What’s going on?” he demanded.

“He tried to steal a candy bar!” the man claimed, pointing at my brother. “I saw him put something in his pocket!”

“No, I didn’t!” Michael protested.

“Yes, you did!”

“Wait a minute,” Bill said skeptically. “He doesn’t even like candy and he doesn’t steal. Why would he steal a candy bar?”

It was obvious then that Michael’s attacker had no idea who he was. As far as he was concerned, this was just another black person – another nigger – to abuse. Bill rushed Michael to a local hospital to have his cuts and bruises tended to.

Mother called us from Alabama to tell us what had happened and we all cried in anger and sadness. How could this kind of thing still happen? If Bill hadn’t been with Michael, he might have been killed. Jermaine was livid, threatening to fly to Alabama and take the law into his own hands. It took some time to persuade him that vigilantism was no way to handle the matter.

Instead, a lawsuit was filed against the store owner. Two girls standing outside had witnessed the beating and one offered to testify on Michael’s behalf. We felt very strongly that racial violence must be stopped, but unfortunately, justice did not prevail in this case. The racist harbored no regrets. In fact, discovering that the black man he’d assaulted was a celebrity only inflamed his hatred. Now he threatened to kill Michael. Bill convinced us that this person was mad, that the threat was quite serious, and that it was better for everyone to drop the action. None of us was happy about this, but there was really no choice.

“My Family” by Katherine Jackson:

Michael usually drove himself to Kingdom Hall and his field-service routes. He’d finally gotten his driver’s license in 1981, at the age of twenty-three. Initially he didn’t want to learn to drive.

“I’ll just get a chauffeur when I want to go out,” he said when I began nagging him about getting his license.

“But suppose you’re someplace and your chauffeur gets sick?” I reasoned.

Finally, he relented and took some lessons.

After he began driving, Michael decided that he enjoyed being behind the wheel, after all. The first time he took me for a ride, he ventured up to Mulholland Drive, a winding road in the Hollywood Hills. It was a hair-raising experience.

“I’ve got a crook in my neck and my feet hurt,” LaToya, who was also in the car, complained afterward. “I was putting on the brakes’ with my feet and ‘steering’ the car with my neck trying to keep it on the road. I was so scared!”

It was white-knuckle time for me, too. Michael drove fast. He also had the same habit that I have: driving right up to the car in front and stopping on a dime.

After that, Michael started going out by himself.

“You shouldn’t go out alone,” I told him. “Get Bill Bray to go with you.”

But Michael wouldn’t hear of it. “I’m tired of having security with me every time I go someplace.”

When he began driving, Michael told me that he would never go on freeways; he thought they were too dangerous. So I was shocked one day when Michael suddenly drove us onto a freeway ramp.

“Wait a minute, Michael, what are you doing?”

“I can drive the freeways now!” he said, laughing. He had changed his mind about freeways when he saw just how long it took him to get around Los Angeles without using them.

Michael’s first car was a Mercedes. Then he bought a black Rolls-Royce, which he later painted blue.

It was in the Rolls that he was stopped one day — not for fans outside the gate, but by a Van Nuys policeman.

“This looks like a stolen car,” the officer said. He didn’t recognise Michael, who wasn’t wearing a disguise that day.

Michael explained politely that he did, indeed, own the car. But the officer went ahead and ran a check on the car, and found that Michael had a ticket outstanding.

The next thing Michael knew, he was sitting in the Van Nuys jail.

Bill Bray bailed him out. I didn’t even know what had happened until he came home.

“You should have asked the officer what a stolen car looks like,” I said after he related his adventure. Perhaps the cop had felt that a young black man didn’t belong behind the wheel of a Rolls.

But Michael was not only put out by the experience, he professed to be happy.

“I got to see how it felt to be in jail!” he exclaimed.

In his song Speed Demon he says “pull over, boy, getcho ticket right” since like white racists referred to black men as “boy” to make them feel less than a man.

"On a personal note, witnessing Jackson's work ethic first hand was an inspiration. Conversations with him later revealed his motivation - he understood that people of colour along with women had to work twice as hard to get half as far. Understanding those metrics he drove himself to work 10x harder."

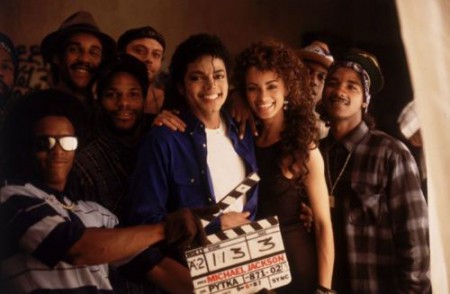

Todd Gray https://www.instagram.com/p/CFzueYvDeqe/

MTV

Walter Yetnikoff, the president of Jackson’s record label, CBS, approached MTV to play the “Billie Jean” video. He became enraged when MTV refused to play the video, and threatened to go public with MTV’s stance on black musicians. “I said to MTV, ‘I’m pulling everything we have off the air, all our product. I’m not going to give you any more videos. And I’m going to go public and fucking tell them about the fact you don’t want to play music by a black guy.’” MTV relented and played the “Billie Jean” video in heavy rotation.

This is an amazing documentary about Michael´s art, that explains racial issues in music and film industry in the USA: Lettre d'amour à Michael Jackson (French with English subt.):

Historic article:

Jermaine Jackson speaks to Charles Thomson about racism and the music industry:

Michael Jackson's Speech at National Action Network, July 6, 2002

Michael Jackson - Speech Against Sony Music 2002

WACKO JACKO

The #racist term "Jacko" is routinely ignored or doesn't register. It DID register with Michael Jackson. He said to Barbara Walters "you shouldn't call me an animal, you shouldn't call me a jacko, I'm not a jacko, I'm Jackson" He knew what it meant.Quote Tweet

Wacko Jacko... it´s not nice!

"Is it because he is black?: What they don’t want you to know about Michael Jackson"

by Christopher Hamilton, Thursday, January 5th, 2006:

For years the media has labeled him ‘Wacko Jacko’. What happened to MJ? Wasn’t he the biggest thing in music at one point? When did he go crazy?

All anyone has to do is look when Michael started being portrayed as ‘Crazy’. It wasn’t during the ‘Thriller’ years. It’s cool being a song and dance man. That’s what they want. Don’t dare become a thinking businessman. Don’t' dare buy the Beatles Catalog. Don’t dare marry Elvis’ daughter. Don’t dare beat the record industry at their own game. Michael started being labeled crazy when he began making business moves that no one had been successful at doing.

Michael took two cultural icons and shattered them to pieces. All our lives, we’ve been bombarded with two facts. The Beatles were the greatest group of all time and Elvis was the King of Rock and Roll. Michael bought the Beatles and married the King’s daughter. (if that ain’t literally sticking it to the man) If I wasn’t a cynic, I’d say Michael did the Lisa Marie thing just to stick it to the people who consider Elvis the King.

The Beatles were great, but they weren’t great enough to maintain publishing rights over their own songs.

Elvis was great, but he didn’t write his songs. His manager, Col Tom Parker, was the mastermind behind Elvis… keeping him drugged with fresh subscription pills and doing all the paperwork.

Michael could do no wrong as an entertainer. ‘Off the Wall’, first solo artist with four top ten singles. ‘Thriller’, the biggest selling album of all time, with a then record seven top ten singles. ‘Bad’, the first album to spawn five number one songs (even ‘Thriller’ only had two number one songs). All this is cool. But that is all you better do. Sing and dance. Michael wanted to be greater. He bought the legendary Sly and the Family Stone catalog and no one really cared. When he bought the Beatles, people noticed. The Sony merger took the cake. Sony, in their eagerness to have a part of the Beatles catalog, agreed to a 50/50 merger with Jackson, thus forming Sony/ATV music publishing. Now, Michael co-owns half of the entire publishing of all of Sony artists. Check out the complete lists of songs at sonyatv.com. A sampling of the songs he owns the publishing rights to are over 900 country songs by artists such as Tammy Wynette, Kenny Rogers, Alabama. All Babyface written songs. Latin songs by Selena and Enrique Iglesias. Roberta Flack songs, Mariah Carey songs, Destiny’s Child’s songs. 2pac, Biggie and Fleetwood Mac songs. In essence over 100,000 songs. “What is this man doing?” None of the greats did this. Not Bono, Springsteen, Sinatra. “Who does he think he is? Get whatever you can on him.”

To ‘get’ someone, you have to attack what they love the most. I’ll say no more on that.

The only man who even approaches MJ in taking on the industry is Prince and to a lesser extent, George Michael. They went after poor George Michael, publicly outing the man as a homosexual. Prince fought hard and made his point, but nevertheless still had to resort to using a major company to distribute his materials. There is nothing wrong with that. Prince would get the lion’s share, but the result were years of being labeled crazy and difficult.

The greatest moment for them was the Sneddon press conference. “We got him.” Never was such glee so evident. Who cares if we have evidence?

Michael was acquitted, did not celebrate, went home and left the USA. Best move ever. Now what is there left for the haters to do? He’s gone. “Gone, what do you mean he moved to Bahrain? Well, how the hell can we get him if he’s not here? Quick, get that columnist to write a series of articles on how MJ’s teetering on the brink of destruction. Oh we did that? Well, what can we do?”

On the outer surface, it appears Michael is not doing anything to make money. Don’t even count the weekly sales of his CDs. 15,000 CDs a week is nothing for Michael. The Sony/ATV catalog is money for Michael Jackson every time he breathes. Serious money. The fact that no one reports on the actual amount is proof of that. They would rather you believe he is broke than tell you the truth. Neverland is still owned by MJ. The family home in Encino is still owned by MJ. Michael still owns the Beatles songs through the merger with Sony as well as full ownership of his own songs. But, hey, that’s our little secret.

Michael Jackson is literally walking in the shoes that no Black person has ever walked in before. If he ever writes an autobiography, it will be one of the most interesting ever. A Black man with no real formal education becomes the most powerful man in the industry, despite hatred, racism, enemies in his own camps and a media willing to be bought to the highest bidder.

If Sony had any sense, right now they should offer to continue the partnership. That’s the only way they will make future money off of Michael’s catalogue. Tommy Mattola did not lose his job with Sony because he was a bad label head. It was a casualty of war. MJ exposed him and Sony had to cut their losses. Companies do it all the time. Notice no one at Sony nor did Matolla himself ever sue MJ for slander. Michael always was loyal to his bosses at Epic/Sony. Back at the 1984 Grammys, he even brought then label head Walter Yetnikoff on stage with him at one point. He’s always thanked Dave Glew, Mattola and others at Sony in his acceptance speeches.

Sony can still do right by Michael, but it may be too late. However, they still should make a goodwill gesture, but how many times do businesses do that? If I were them, I’d still want MJ as an ally, not as an enemy. It is/was a mutually profitable merger.

I’d be scared as hell if I was an enemy of MJ while he is with the multi-billionaires overseas. Believe me, they aren’t just over there discussing designer clothing. A conglomerate is in the making.

One last note, these facts that I write here should not be the only times you hear this, but the sad fact is it probably is. I was worried that Michael would go down because of the uncertainty of the jury. That’s playing unfair. If I’m presenting these facts here at EURweb, you can believe the media knows it already as well. They aren’t salivating over everything MJ related just because he made ‘Thriller’. They know what’s up. Think about it. That’s why I laugh when I see shows like BET’s ‘The Ultimate Hustler’. We all know who that is. (How can Damon Dash know who the ultimate hustler is anyway? He lost Roc-a-fella to Jay-Z)

In the end, Michael won’t be known for being an alleged child molester. He won’t be known for ‘Thriller’. He will be known as the man that fought the record industry and won and lived to tell the tale. That is a book worth buying.

Christopher Hamilton is a freelance entertainment writer. He can be reached for questions or comments at mrcjhamilton@hotmail.com

The New Lynching of Michael Jackson: Dan Reed’s Leaving Neverland May, In Fact, Leave Blood on Many Hands

America has a long and sordid history of lynching or unfairly convicting African-American men based on the false allegations of white accusers. The names known to history echo loud and long — Robin White, Emmett Till, Charlie Weems, Ozie Powell, Clarence Norris, Andrew and Leroy Wright, Olen Montgomery, Willie Anderson, Haywood Patterson, Eugene Williams (the latter nine known collectively as “The Scottsboro Boys”) to contemporary names such as Vincent Patton, still serving time in Angola Prison despite the fact that his white accuser later confessed that “all black men look alike” to her and therefore she could not even say with certainty that Patton had raped her. And these cases do not even begin to include the many whose names have long been lost to history; those who paid the ultimate price for the paranoid fears of a Jim Crow-era America. “We currently live in a world of fake news and alternative facts,” wrote Martinzie Johnson in an excellent think piece titled “Being Black in a World Where White Lies Matter.” Martinzie then states, “white lies have tangible consequences.”

The current hype that has been built around Leaving Neverland, a film directed by Dan Reed and funded and distributed by HBO in the U.S. and Channel 4 in the U.K., may appear deceptively at first as an important film for the #MeToo era, highlighting the alleged sexual abuse that Michael Jackson inflicted on two young boys who idolized him and fell-by grand and parental design-into his circle. At least, that is according to the hype that has been drummed up around it. But a closer look reveals many disturbing reasons to argue that this agenda-driven film has little to do with either journalistic integrity or concern for sexual abuse victims. Instead, there are many justifiable reasons to argue why this film is simply a new twist on the age-old concept of lynching a black man based on white lies. The fact that it is a black man who also just happened to be one of the most beloved and powerful figures in entertainment is, of course, the very matter at the heart of the film’s controversy, along with the fact that we are into the tenth anniversary of his passing. At a time when Michael Jackson’s life should be the subject of fond remembrances and reflections on his artistic legacy, we instead get this, the equivalent of a posthumous, 21st century lynching based on nothing but the uncorroborated testimonies of two men whose civil case against his estate has already been dismissed, not once but twice.

Why is the “woke” crowd so determinedly asleep at the wheel on this? And an even more troubling question: Why are so many of the most influential journalists in the U.S. and U.K. enabling it? Dan Reed’s controversial film has indeed accomplished one positive goal even before its scheduled broadcast, although it may not be the goal he intended.

For sure, the film has helped shed much needed light on the underbelly of #MeToo, revealing some startlingly dark truths about who the movement is designed to protect-and who it is willing to sacrifice.

___________________________________________

“Can You Feel It?”

The Triumph (1981)

Jackson continued to fight racism and other forms of prejudice throughout his long career, and these efforts only intensified after he was accused of child sexual abuse. In fact, his later work is among his most powerful and important. However, much of this work is so revolutionary that we don’t yet even recognize it as art. Developing an appreciation for his work and the full measure of his artistic achievement has implications not only for how we interpret Jackson and his legacy but also for how we see art and its potential for social change. However, to fully grasp Jackson’s ideas and the transformative power of his art, we must first gain a better understanding of the cultural undercurrents he was fighting against.

The Sensations of Racism

This disparity between our ideals and our impulses was perhaps the central conflict of my childhood. I grew up in Charlotte, North Carolina, in the 1960s, at a time when the Civil Rights movement dominated the local and national news. When I was in elementary school, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School District became the first in the nation to integrate its schools through mandatory bussing, and suddenly the demographics of my school shifted dramatically. In second grade, my teacher and all of my classmates were white. In third grade, my teacher and many of my classmates were black, and my understanding of the world expanded a bit. The idealistic teachers at my school — both black and white — worked hard to make integration a success, and so did my parents. While many parents in my all-white neighborhood complained bitterly about bussing and threatened to move their kids to private schools, my parents told me that integration was important and I should be proud to be part of it.

They also taught me to admire the black men and women I saw in the news who were fighting for the right to vote or attend better schools or simply sit at a lunch counter. While my parents tried to shield me from the worst images, I occasionally saw photos or news footage of protesters being beaten with clubs or attacked by police dogs, and I can still remember the shock of that. I would look at the protester’s frightened but determined faces and flinch in fear for their safety, and through their suffering I felt the stirrings of empathy for people I didn’t know, whose life experiences were very different from my own. As I learned more about the South’s long history of racial oppression, my admiration became mixed with a sense of horror and shame for the injustices the protesters were fighting against. When my Sunday School teachers talked about original sin, I thought they meant slavery.

In this way, I was taught to question the past and believe in the equality of all people, black and white. But alongside these high ideals ran an undercurrent of counter-narratives, the repeated whisperings of stories much older than those my teachers told me. These whispered stories insisted that black bodies and white bodies were essentially different: that black skin wasn’t just darker than white skin but thicker, more resistant to injury, and less sensitive to pain than white skin, so that black bodies didn’t feel the impact of a billy club or the blast of a fire hose or the bite of a police dog in the same way a white body would. These stories also insinuated that the sweat and odors of white bodies were fundamentally different than those of black bodies, and they implied that proper white bodies didn’t sweat or smell at all. This deep divide between the inspiring stories we heard on the news and the enduring stories we heard whispered in the background created an internal split for many Southern white children. The public stories influenced our ideas about the lofty goal of racial equality, but the whispered stories shaped our feelings about black bodies and black people.

This divide existed from the founding of the United States. In the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson boldly declared that “all men are created equal.” But in Notes on the State of Virginia, he wrote that blacks “seem to require less sleep” than whites, are “more tolerant of heat,” and have “a very strong and disagreeable odour.” Jefferson speculated about psychological differences as well, writing that blacks apparently suffer from “a want of fore-thought” and feel a lusty “eager desire” for “their female” rather than love. He also wrote that “their griefs are transient” — a convenient belief for a slave owner.

While the white adults I knew in the 1960s tended to be more circumspect in stating their opinions about racial differences than Jefferson was, the racist notions that he documented more than two centuries ago persisted. Underlying this entire belief system was an insistence that blacks and whites were essentially different, and this had an impact on how white children perceived black people — even those they knew well. For example, when I was in college a white friend told me she had been raised in part by a black housekeeper and loved her. She was an important part of her childhood. But one day the housekeeper cut her hand, and my friend was astonished to see that her blood was red. She had assumed her blood was as dark as her skin. My friend was a young girl when this happened, but years later she could still remember the emotional jolt she felt at that moment. The stories she’d heard throughout childhood had convinced her that racial differences weren’t just superficial but fundamental: that they extended to the blood in our veins and the very essence of who we are.

Later, as white girls of my generation left childhood and became teenagers, we were introduced to another, very specific type of narrative: stories of abduction and rape and murder. This was before the concept of date rape, back when the word “rapist” meant a stranger lurking in the dark. And in the American South, especially, that stranger was invariably black. In news reports as well as the whispered stories of older white women, the message was always the same: white women needed to protect themselves from the sexual threat posed by black men.

Looking back, I see all of these stories as playing a decisive role in perpetuating racism, influencing not only how young white people thought about race but, even more importantly, how we felt about race. George Orwell describes a similar phenomenon in terms of class prejudice in 1930s England. In The Road to Wigan Pier Orwell writes that while doing research on conditions among the working class, he was forced to confront the issue of class prejudice — his own internalized class prejudice:

Here you come to the real secret of class distinctions in the West — the real reason why a European of bourgeois upbringing, even when he calls himself a Communist, cannot without hard effort think of a working man as his equal. It is summed up in four frightful words which people nowadays are chary of uttering, but which were bandied about quite freely in my childhood. The words were: The lower classes smell.

That was what we were taught — the lower classes smell. And here, obviously, you are at an impassable barrier. For no feeling of like or dislike is quite so fundamental as a physical feeling. Race-hatred, religious hatred, differences of education, of temperament, of intellect, even differences of moral code, can be got over; but physical revulsion cannot.… [E]ven “lower-class” people whom you knew to be quite clean — servants, for instance — were faintly unappetising. The smell of their sweat, the very texture of their skins, were mysteriously different from yours. (emphasis his)

Orwell’s frank talk of a culturally produced “physical revulsion” may make us uncomfortable, but he’s broaching a crucial element of racism and classism that must be addressed if we are ever to eradicate prejudice — namely, the powerful influence of affect. The biases Orwell identifies are not based on reason but instead arise from visceral reactions that have been carefully cultivated for centuries. One way these feelings and physical sensations have been perpetuated across generations is through the kinds of whispered stories that populated my childhood and teenage years. The roots of these stories stretch back centuries, to the earliest days of American history.

Poster c 1800, Library of Congress (left), and Tom Lovell, illustration for The Last of the Mohicans (right)

For example, in the 1860s the Central Pacific Railroad Company recruited thousands of Chinese men to come to the U.S. to work on the first transcontinental railroad. Other Chinese laborers were recruited to work in the mining industry. However, by the 1870s white Californians began to feel intense anxiety over the size and economic success of the Chinese immigrant community, which by the end of the decade comprised nearly ten percent of California’s population. White legislators responded with America’s first drug law, which criminalized opium and explicitly targeted Chinese men. The justification for this law was protecting the sexual innocence of white women, as federal judge Frederic Block succinctly "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);" target="_blank">described: “It was believed that Chinese men were luring white women to have sex in opium dens.” These fears led to attacks on Chinese individuals and communities, confiscation of property, and an abrupt end to immigration from China.

A parallel movement occurred in the 1930s, but this time the target was Mexican immigrants. As with Chinese workers, Mexican laborers had been actively encouraged to enter the U.S. to meet a labor shortage. However, when the Great Depression led white workers to feel increased job anxiety, those Mexicans laborers were no longer welcome and marijuana laws were enacted against them. As Sean Hogan explains in “Race, Ethnicity, and Early U.S. Drug Policy,” newspapers stoked intense anti-marijuana sentiment over the image of “drug-crazed Mexicans ravaging women and children in the southwestern United States,” despite a 1930 review of crime records that showed below-average rates of crime and delinquency among Mexican immigrants. So again, economic and cultural anxieties led white men to prosecute and persecute non-white men, with the justification that they were protecting the sexual innocence of white women and children.

However, nothing galvanized the white imagination quite like the image of a white woman outraged by a black man. As journalist Ida Wells described in an 1892 pamphlet, "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);" target="_blank">Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, falsely accusing black men of raping white women was used as a psychological tool to enflame white mobs and justify their actions as they attacked, tortured, and murdered black men. As Wells wrote,

[N]ot less than one hundred and fifty have been known to have met violent death at the hands of cruel bloodthirsty mobs during the past nine months.

To palliate this record … and excuse some of the most heinous crimes that ever stained the history of a country, the South is shielding itself behind the plausible screen of defending the honor of its women.

Wells suggests these vicious lynchings weren’t simply isolated acts of brutality but instead had an over-arching political purpose: to suppress freed black people, especially black men, following the abolition of slavery. As she writes, “the whole matter is explained by the well-known opposition growing out of slavery to the progress of the race.”

The charge of rape proved an effective justification for white-on-black violence, according to Wells, because “the crime of rape is so revolting” to both blacks and whites that “Even … Afro-Americans … have too often taken the white man’s word and given lynch law neither the investigation nor condemnation it deserved.” Wells warned her readers that this rationalization had become so prevalent by the end of the 1800s that “it is in a fair way to stamp us a race of rapists” — a prediction that proved prescient. The evidence suggests that black men did in fact come to be perceived as sexual predators, and the focus of irrational fears by white men and women because of that misrepresentation.

These fears extended throughout Restoration and up to the present day. For example, the U.S. experienced waves of anti-cocaine hysteria beginning in the late 1800s and enacted a series of repressive laws against cocaine in the early 1900s — a pattern that repeated itself in the 1980s against crack cocaine. These laws and the social debate surrounding them targeted black men in much the same way that opium and marijuana legislation targeted Chinese and Mexican immigrants. However, the “campaign” against black men was “even more vicious,” according to Hogan: “The imagery and rhetoric of the cocaine-crazed southern black man … spuriously validated an increase in violence against blacks in the South.” As with the crusades against opium and marijuana, the image of non-white cocaine addicts sexually abusing white women and children was used to fulfill a political purpose, as Hogan explains:

The … hysteria related to cocaine and African Americans was … an invention of white society, a myth created in an environment of fear and prejudice … with the intent of maintaining a dominant and oppressive status quo. Depicting African Americans as cocaine-crazed sexual deviants, and a threat to the purity of white women and children, served this end.

So once again, the “myth” of non-white sexual predators attacking white women and children was used to repress a vulnerable minority population — in this case, black men attempting to emancipate themselves from centuries of racial oppression.

But why exactly has the narrative of non-white men as beasts and rapists preying upon white women and children survived for so long, and been repeated so many times? Part of the answer may simply be property rights, a driving force behind much of American history. As Limerick writes, “If Hollywood wanted to capture the emotional center of Western history, its movies would be about real estate.” The 2006 documentary Banished: How Whites Drove Blacks out of Town in America makes this connection clear. It begins with chilling charcoal sketches of lynched black bodies hanging from trees and other scenes of white-on-black mob violence, interspersing them with stark lines of explanatory text:

From the 1860s to the 1920s, in more than a dozen counties, white Americans violently expelled their black neighbors.

The pattern was eerily similar: an alleged assault of a white woman, the lynching of a black man, and the forced expulsion of an entire black community.

The property the African Americans had to leave behind — homes, livestock and acres of land — was lost forever.

The film then looks at three cases of banishment — in Georgia, Missouri, and Arkansas — where a black man was accused of raping a white woman, and that charge was used by whites as justification to terrorize and destroy a thriving black community. Local whites then confiscated the property that had belonged to black residents.

Perhaps the most egregious example of whites using a dubious claim of sexual assault as a pretext for destroying a successful black community is the Tulsa massacre of 1921. A shy black teenager, Dick Rowland, apparently stumbled while entering a downtown Tulsa elevator and fell toward the young white elevator operator, Sarah Page. She reacted with fear and surprise, and he was arrested and accused of accosting her. Page herself refused to press charges, and several prominent white citizens came forward on his behalf. However, rumors spread and an inflammatory article in The Tulsa Tribune accused Rowland of either raping or attempting to rape Page in the elevator.

A mob of about 2,000 whites gathered at the courthouse and violence erupted. According to a New York Times "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);" target="_blank">article, the Tulsa riot “may be the deadliest occurrence of racial violence in United States history,” with “up to 300 people … killed and more than 8,000 left homeless.” A 40-block area of black homes and businesses known as the Greenwood district was completely destroyed by looting and fire. Before the riot, the Greenwood district was one of the most affluent black communities in the U.S. — an area so prosperous Booker T. Washington christened it Negro Wall Street. As historian Scott Ellsworth notes in the documentary The Night Tulsa Burned, this created a kind of racial envy that led to white-on-black violence in Tulsa and other successful black communities:

The important thing to remember about race riots during this period is that they are characterized by whites invading black communities … attacking black businesses, attacking black homes.

Ellsworth goes on to explain that “For some white people, a black person with any wealth, then as well as today, is something that created jealousy.” In Tulsa as well as many other communities destroyed by angry white mobs, a false allegation of sexual assault was the pretext used for murder and the destruction or theft of black wealth.

The implications extend well beyond the loss of property, as Derek Litvak explained in a Washington Post "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);" target="_blank">article about the importance of land ownership in the U.S. and South Africa:

[L]and has long been a primary source of independence, especially for black people. After the Civil War, land ownership was essential to fundamental, and possibly lasting, change — which is precisely why it was repeatedly denied to freed people, who understood land ownership as key to emancipation.

Using lynch law as a violent means to seize black property robbed black citizens of their liberty as well as their land — a loss of economic independence that could take generations to restore.

However, the image of the black rapist has historically been used in more subtle ways as well: not only to destroy successful black businesses and communities and confiscate black property, but also to unite white men and women against non-white men and reinforce white male authority. For example, The Birth of a Nation (1915) is frequently cited as one of the most influential films in U.S. history, as cultural critic Joe Vogel "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);" target="_blank">describes:

It ushered in a new art form — the motion picture — that transformed the entertainment industry. … Birth became the most profitable film of its time — and possibly of all time, adjusted for inflation. It was the first film to cost over $100 thousand dollars to make, the first to have a musical score, the first to be shown at the White House, the first to be viewed by the Supreme Court and members of congress, and the first to be viewed by millions of ordinary Americans. It was America’s original blockbuster.

According to Ralph Ellison, it also “forged the twin screen image of the Negro as bestial rapist and grinning, eye-rolling clown.”

The film is set during and immediately after the Civil War, and the climax centers on the twin narratives of a black officer attempting to rape a young white woman named Flora (she commits suicide rather than succumb to him) and a scheming black politician — ironically named Silas Lynch — attempting to coerce another young white woman named Elsie into marrying him (she is rescued by the Ku Klux Klan). The conflict is resolved when the Klan rides in on horseback to the sounds of triumphal orchestral music to restore order — meaning white supremacy — in part by killing the black officer who accosted Flora and dumping his body on Lynch’s doorstep.

The film ends with a double wedding: a white brother and sister from the South marry a white brother and sister from the North. Significantly, the Southern bride is Elsie. The message is clear. What will reunite whites from the North with whites from the South and restore a nation divided by civil war is their shared fear of black rapists — or more symbolically, their shared fear of black men usurping positions traditionally held by white men.

The narrative of the black rapist therefore takes on significant political implications in The Birth of a Nation, and those implications still carry significant weight today, as the election of Donald Trump makes clear. From the earliest days of his campaign Trump explicitly targeted men of color as sexual predators. For example, in his June 16, 2015, speech announcing his candidacy, Trump notoriously claimed that Mexican men are “bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.” And he has returned to this playbook again and again. Repeatedly during his campaign and continuing through his presidency, Trump has characterized men of color — not only Mexican but also black, Muslim, and American Indian men — as predatory criminals.

However, Trump is by no means the first politician to stoke these kinds of racist fears. Candidates throughout U.S. history have found that evoking subliminal fears of non-white men as brutes and rapists can be a very effective political tool, especially in times of heightened cultural and economic anxiety. For example, the early 1980s was a period of overlapping crises, with double-digit inflation, high unemployment, violence in the inner cities, an energy crisis, a savings-and-loan crisis, and a “crisis of confidence,” as President Carter termed it. And significantly, two of the biggest stories of the decade — Willie Horton and the Central Park Five — centered on men of color accused of raping white women. Even more significantly, candidate George H.W. Bush and aspiring candidate Trump then leveraged these two cases for political capital.

One person who seems to have learned important lessons from how the Bush campaign politicized the Willie Horton case is Donald Trump. The following year, Trump began his first foray into presidential politics, telling Larry King in a 1989 "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);" target="_blank">interview that he was putting together “a presidential exploratory committee.” And in a move that mimicked Bush’s strategy, Trump began by seizing on the case of the Central Park Jogger, enflaming public opinion against five 14- to 16-year-old boys accused of brutally beating and raping a white woman running through Central Park. Four of the accused teenagers were black and one was Latino. Trump ran a full-page ad in all four of New York City’s major newspapers calling for the death penalty, and he appeared on talk shows — including another visit to Larry King Live — where he explicitly tried to stir up public animosity and even hatred. As Trump told King, “I hate these people. Let’s all hate these people, because maybe hate is what we need to get something done.”

One of the Central Park defendants, Yusef Salaam, later "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);" target="_blank">described Trump as “the fire starter” in stoking public anger against the teens, saying, “he lit the match.” Salaam also explicitly linked Trump’s actions to America’s long, shameful history of white mobs lynching black men accused of raping — or even looking at — white women. As Salaam said, “It was the scariest, scariest time in my life…. Had this been in the 1950s, I would have had the same fate as Emmett Till.… I would have been hung.” In 2002, the convictions of the Central Park Five were vacated after another man confessed to the crime and DNA evidence exonerated them. However, Trump discounted the evidence and continued to question their innocence during his 2016 presidential campaign. He also repeatedly stirred public opinion against non-white immigrants, accusing them of rape, murder, and other violent crimes.

So while Bush and Trump are very different politicians in terms of their temperament, intelligence, experience, and principles, historical evidence suggests that they both owe their presidency to the same poisonous well: their willingness to enflame white fears of non-white men as sexual predators. However, looking back through American history, the problem is not so much Bush or Trump. Rather, it is the racist fears that propelled them to victory — fears that have served a subtle but potent political purpose for generations, especially since the abolition of slavery.

But why are these racial anxieties so effective? The threat posed by black men (or Latino or Asian or Muslim men, or any targeted group) was not a pressing national crisis in 1988 or 2016, and it never has been. So why has this hysterical narrative of non-white sexual predators had such an out-sized political and cultural influence, and for so many generations? I believe the answer lies in affect, the complex web of responses — both psychological and physiological — that together form what we tend to think of as our “gut reactions.” Specifically, these stories stoke fears so powerful they cause a visceral reaction, and in that way help create and perpetuate white America’s “gut” response to racial signifiers.

Consider the rather hackneyed scenario of a white woman walking alone down a city street and seeing a black man walk toward her. Because of the pervasive narrative of the non-white sexual predator, she might look at him and think about a specific scary story (for example, about Willie Horton or the Central Park Five or hundreds more stories like them) and feel a sense of uncertainty or fear. Even more insidiously, she might not consciously think about any particular story at all, but still look at that approaching figure and experience a quickened pulse, an involuntary intake of breath, and a vague feeling of apprehension without knowing why. That’s affect — when stimuli cause immediate psychological and physiological reactions before the conscious brain has time to process what is happening or why.

These sensations are extremely difficult to overcome. For example, on March 18, 2008, in perhaps his most important "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);" target="_blank">speech on race, presidential candidate Barack Obama described his white grandmother as “a woman who helped raise me, a woman who sacrificed again and again for me, a woman who loves me as much as she loves anything in this world.” However, he went on to say that she “once confessed her fear of black men who passed by her on the street.” Even her deep love for her grandson, who lived with her for much of his childhood, could not eradicate this fear.

This kind of “gut reaction” is racism at its most raw and most intractable because you can’t reason with it. How do you debate a physical sensation? It feels true at a deep, physical level. Even if this hypothetical white woman is sufficiently self-aware to question her own reactions and try to suppress or alter them, it’s almost impossible for her to do so because they are spontaneous — both pre-cognitive and pre-verbal — and therefore happen before her conscious mind has a chance to mediate her responses.

These psycho-physiological reactions are man-made: a learned reflex. They result from the thousands of stories and comments and images a person experiences over a lifetime, especially in childhood. But because these reactions happen so quickly and because they involve physical sensations, they don’t seem to be man-made. Instead, they feel instinctual or natural — as natural as the body itself — and therefore they seem to exist outside language, outside culture, outside the reach of reason and logic. The perception that these spontaneous physical responses are real and natural is precisely what makes them so resistant to change, and so very difficult to fight.

Seen in this light, the persistent narrative of the black or brown sexual predator plays an insidious cultural function: it helps create the “gut reaction” many white Americans feel toward men of color. This narrative is so pervasive — and has been, for so many generations — that it subconsciously shapes how many white Americans perceive and emotionally respond to black men and other men of color. It helps explain why many white Americans tend to see men of color as scary and guilty of some vague crime even when they’ve done nothing wrong — for example, why a white woman managing a Starbucks would call police to report two black men sitting in her coffee shop or numerous other instances of #LivingWhileBlack. It may also help explain why white police officers too often display an inexplicable rage towards men of color accused of relatively minor crimes, and why they repeatedly use excessive force against black men especially.

Don’t Stop ’Til You Get Enough (1979)

Jackson was able to accomplish this unprecedented feat in part because of his popularity as a child star. White America felt a deep affection and familiarity with him from seeing him on stage from such a young age, and this helped soften their fears of a grown Michael Jackson. But this accounts for only part of his success. Jackson also worked to maintain a persona that was as nonthreatening as possible to white America — a lesson Gordy had schooled him in very thoroughly. Jackson tended to be guarded in interviews, steering clear of politics as Gordy had taught him, and he emphasized the childlike parts of his personality well into adulthood, even adopting a soft voice that was somewhat higher than his natural speaking voice. He also appeared rather shy and deferential in interviews with white critics especially, though he could be livelier with black journalists, as in his 2007 "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);" target="_blank">interview with Ebony magazine.

Jackson therefore maintained a carefully calibrated balancing act in how he presented himself to white America, pushing the boundaries in some areas while assuaging white fears in others. This is clearly evident in how he performed his sexuality — and his public displays of sexuality were to some extent a performance, as he explained to biographer Randy Taraborrelli in a 1977 interview:

I think it’s fun that girls think I’m sexy… But I don’t think that about myself. It’s all just fantasy, really. I like to make my fans happy so I might pose or dance in a way that makes them think I’m romantic. But really I guess I’m not that way.

Through his concerts and films as well as his public persona, Jackson presented a radically new vision of black male sexuality: steamy, sensual, and very desirable to young women of all races (as millions of fans around the world can attest) but also sweet, sensitive, innocent, even naive. White America had never seen anything like this before, and it took the nation — and the world — by storm. He became by many accounts the most famous man in the world and an acknowledged sex symbol by teens of all races.

We tend to trivialize teen idols, so it may be difficult to grasp the full significance of what Jackson accomplished. By establishing his own body — a black man’s body — as an object of desire, he set off subterranean tremors in the white psyche. His body inspired sensations that had rarely been confessed by whites before: namely, that they found a black body sexy and desirable. In this way, Jackson altered or at least complicated the subliminal responses of white audiences to black bodies and black people, especially black men. This is historic: a pivot point in American history. He upended established conventions and challenged existing power structures on many different fronts — for example, through his immense fame, wealth, and professional success — but the psychological changes he brought about in the hearts and minds of white Americans were perhaps the most profound and far-reaching of all.

However, Jackson’s rise as a sex symbol placed him in a precarious position. Suddenly, he was a black object of white desire in a deeply racist country that sees black men as threatening and potentially corrupting white women and children. It was a risky, even dangerous position to be in. He received death threats, and his body became an object of white fascination, even an unhealthy obsession. In effect, his body became the site where cultural conflicts played themselves out, particularly between white America’s forbidden desire for the taboo or exotic and their fear of the black sexual predator.

But Jackson wasn’t simply a passive object of white fear and desire. He was also a powerful artist — one of the most influential artists of our time. Through his art, he took control of the narratives that were being projected onto him and then disrupted and diffused them in complex ways. This aspect of his art functions at a deep psychological level: the level of affect. It bypasses the conscious mind — in fact, it doesn’t make much sense to the conscious mind — and instead speaks directly to the subconscious, destabilizing and reconfiguring the fears white Americans have projected onto non-white men for centuries.

Jackson’s methods are complicated and elusive, and they became even more sophisticated as he matured as an artist. Therefore, the full power of his art is difficult to measure and comprehend. However, if we take the time to look carefully at his work, we can begin to uncover the artistic strategies he developed for neutralizing a global audience’s affective responses to racial cues — in effect, rewiring their “gut reactions” to difference. In this way, he was able to fight racism at its deepest, most primal level. Investigating Jackson’s art therefore has profound implications not only for how we see his work and legacy but also for how we see art more generally and its potential to bring about lasting social change.

Note: This essay is the first of a four-part series. "); background-size: 1px 1px; background-position: 0px calc(1em + 1px);" target="_blank">Part 2 takes a close look at some of Jackson’s important early work, including Thriller, to discover how he addressed white fears of black men in psychologically complex ways.

Source: medium.com/@willa.stillwater/can-you-feel-it-2701661c5ad3

Jackson Family

Double Standard: A Look at the 2004 Super Bowl Halftime “Nipplegate” Scandal and the Aftermath.